The post also appears at Teaching Artist Journal’s ALT/Space.

Creating a permanent place for the arts in public education requires some adjustment between the two in order to create a fit — a whittling process that usually affects the art more than the public institution within which it’s finding a home. Given the current trends in educational reform, with emphasis on standardized testing, accountability, and data-driven funding, any maneuvers to maintain the arts in education bring up some good questions:

What are students actually learning? How do we know they’re learning it? How does arts instruction support other or lifelong learning? What kinds of data can we develop to prove learning and transfer?

The process of answering these questions – of assessing student learning – is one of the steps toward shaping the round peg of arts education into the square holes of public education. However, it’s essential to answer them without sacrificing the core qualities that humans gain from their artistic endeavors: expression of self, creativity, passion, and vision.

Which is to say it’s April, and I’m thinking hard about teaching and learning in a comprehensive, sequential dance program – because it’s assessment time in dance class! I need to gather data on what my students know and can do, without them feeling the discomfort of having their creativity squeezed and shaped to fit a particular mold.

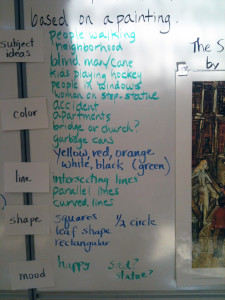

This week, for spring vacation, I scored students’ performance assessments. Our dance program includes all students from kindergarten through fifth grade, at a rate of about one hour per week. Instruction consists of lots of creative movement, improvisation using the basic vocabulary of movement (categories of space, time, energy, body), choreography, and cultural dances from around the world. The performance assessment that students complete in fifth grade asks them to choreograph a solo dance based on either a poem or a piece of visual art, perform it for videotaping, and write briefly about their movement choices. The assessments are scored in three categories of Creating (choreographing a beginning, three different movement phrases, and an ending), Performing (performing their dance without interruption, with clear energy and space choices, and maintaining their focus), and Responding (explaining movement choices for three ideas or images from the poem or art).

Results from these assessments provide plenty of data concerning the first two questions above: “What are students actually learning?” and “How do we know they’re learning it?” I know it because a performance assessment asks them to do it: translate ideas into choreographed movement, perform their dance with confidence, and explain their ideas. And I know they’re learning because the results are generally good. But the results also provide plenty of fuel for reflection.

In one 5th grade class:

~25% of students (7 out of 27) met all criteria perfectly (including four boys and three girls; one African-American student, one African student, four students from SE Asian heritage, and one Caucasian). It’s a relief when I see students of various backgrounds succeeding!

~81% of students (22 out of 27) achieved levels of either competent or proficient.

So… many kids are learning in this class, but what about the 19% (5 students out of 27) that scored as emerging rather than competent dancers (an average of under 3 points on a 4-point scale)? They indicate plenty of room for instructional improvement. Looking at them individually, I notice two (a boy and a girl) who began dancing just this year, one boy whose religion disapproves of dance, and two other boys who should have done better – but didn’t. These last two boys are particularly troubling, providing plenty of food for thought in the months to come, as I reflect on ways to improve what they learn.

And what about trends visible as weaknesses throughout the class?

~9 students were either missing a third movement phrase in their choreography or their third phrase was too short. Note to self: keep teaching them how to build movement phrases with more than one movement!

~10 students didn’t understand about making their beginnings and endings express the ideas in their dance; instead they created beginnings that said “I’m ready!” and endings that said “OK, I’m done now!” Note to self: start working on stronger beginnings and endings in third grade, at the point when I’m really emphasizing the beginning-middle-ending sequence.

~3 couldn’t explain their movement choices. Note to self: check over the response sheets quickly and collect verbal responses if there’s an English-language-learning or writing problem.

~5 students performed with limp energy and minimal use of space. Note to self: get started early in the year on self- and peer-assessments, so they understand how their movements are coming across.

Reflection will continue, even though assessments are finished for this year. And there are questions that these assessments don’t answer, including the effect of arts instruction on other learning. For this, we’ll need new and different measures. But for now, while thinking about ways to do better next year, these students and I return to the exciting work of making art and another excellent question:

Can 380 students collaborate to put on an end-of-year performance for families and friends?!

Yes, most likely. Starting Monday. And happily, building a performance is not at all about making disparate parts fit – it’s at the core of dance, with excitement building daily!

This is great, Meg – a true glimpse into our lives of teaching and assessing public school dance, with a raw and honest self-reflection. Thank you for being a strong voice!